“Since we have lost our beards, we have lost our souls” – Spanish proverb

“The moustaches are glorious, glorious. I have cut them shorter, and trimmed them a little at the ends to improve their shape. They are charming, charming. Without them, life would be a blank”. – Charles Dickens in a letter to Daniel Maclise

The Victorians loved a good beard. Darwin, Marx and Watts had great beards, Bazalgette had a wonderful set of mutton chops, Dickens had a goatee, Prince Albert had a moustache, and the great emancipator, Abe Lincoln, was the first president of the USA to sport facial hair. So why did the Victorians love their whiskers so much?

Well, partly it was fashion, of course, but it went much deeper than that. Surely religion couldn’t be involved, could it? In 1847 Reverend William Henry Henslowe published a pamphlet entitled (deep breath)

“Beard Shaving and the Common use of the Razor, an Unnatural, Irrational, Unmanly, Ungodly and Fatal Fashion among Christians”

To cut a long and very dreary story short, Rev’d Henslowe preached that God made man in his own image, and that image included a beard. Shaving off your beard was ‘contrary to His good will and pleasure.’ He also raises a damning finger of complaint against the tools of our trade, saying:

“It is impossible to calculate the amount of suicides, homicides and murders perpetrated during the last thirty years, by means of the disgraceful practice of shaving, and the common use of the razor. Is not the razor, therefore, on this account alone, as much deserving to be deprecated by Christian men and philanthropists, as the sword?”

To try and back up this claim, Henslowe cites the instance of a Prison chaplain who, due to his heavy debts, committed suicide during the night by cutting his own throat with – you guessed it – a razor. Had the razor not been in the room, points out Henslowe, the chaplain would still be alive. In a catchy part of his sermon he warns the youth of the world against the sin of shaving:

Heedless youth, give ear,

Earthly Fashions fear –

Never let come near,

Shaving knife and gear –

Let the young down grow,

On thy lip – below –

Wherever it doth show,

Else thou shalt suffer woe.

One supposes that the Sharpologist website, in Henslowe’s eyes, would be utter heresy, and torn from the internet forthwith, before being righteously burned in the fires of hell.

As much as we mock the work of the good reverend, which sinners can read in its entirety for free on Google Books, here: http://books.google.co.uk/

But surely not every bearded man of the nineteenth century was super-religious? No. Dickens, for one, was not a religious man, but sported his famous goatee beard in his later years. So there must have been other reasons for facial hair amongst Victorian gents. One of the more bizarre reasons for a beard (considering how forward-thinking and revolutionary the Victorians were) was one of health. In large cities that were plagued by a constant pall of industrial smoke hanging in the air, as well as disease epidemics caused by unsanitary conditions in slums, beards were seen – by some – as a kind of filter that would catch airborne germs – or miasma – before you were able to breathe them in. The beard would also act as a scarf, some said, keeping the chill off your neck on those cold winter days, and leaving you less prone to illnesses. Women, meanwhile, felt none of these benefits, and it is for this reason that women were seen as the gentler and frail sex, with far weaker constitutions than men. Whilst gents could stride about the city breathing in pure, filtered air and showing how close to God they were, women had to stay at home, being meek, with no way of showing how much they loved going to church and reading the good book.

So, that’s a religious reason not to shave, and a health reason not to shave. What else can there be?

Much like today of course, there was the reason of fashion. From the 1840’s to the 1870’s different facial hair styles came in and out of fashion, from mutton chops to dundreary whiskers, Piccadilly weepers to a Van Dyke beard. But what was the reason for this change? During the regency and pre-Victorian period (1795 – 1837) a nice smooth face was de rigueur amongst men of all classes, so why did people change their mind?

Well, many people saw shaving as a little bit effeminate. By the 1880’s facial hair was seen as the look of traditionally manly-men. Manual workers had facial hair, which they sported as they lifted heavy picks and hammers or carried bricks. Clerks, meanwhile, who sat behind desks in drafty offices holding nothing heavier than a pencil, were clean shaven. The long and short of it was that being clean shaven was for weaklings. This was proved by the British army, who, having occupied India, had seen the natives mock their pale, smooth and lady-like beardless faces. The British decided the best way to fit in and gain the trust of the Indian people was to copy them. So began Britain’s love of Indian food, as well as the opinion that facial hair was a symbol of masculinity.

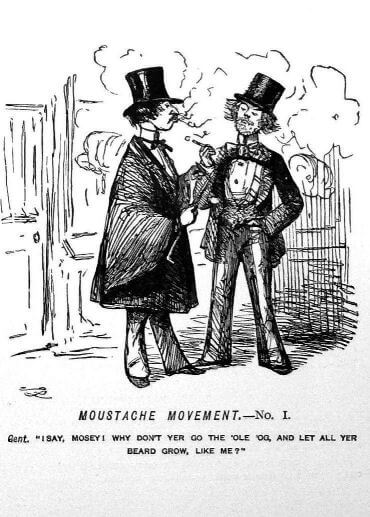

By 1884 the opinion that facial hair was required by anyone not of the same disposition as Oscar Wilde was complete, and to prove it there was even a play entitled ‘The Moustache Movement’ which made great fooling of the ‘fact’ that all bare-faced men looked alike, whether they be ‘Duke or Dustman’.

By the end of the Victorian era and the turn of the twentieth century, beards generally began to wane in favour of neat moustaches; a trend which lasted virtually until the end of the 1980’s, when the number of mustachioed men walking down the street finally began to decline because…why? Certainly by then the religious and health reasons for sporting facial hair had been kicked into the long-grass, and so we are left with fashion. By the onset of the 1990’s it just wasn’t fashionable to have a moustache any more, although a few men clung on to them as though they were the very source of their youth, and that by shaving them off they would somehow be admitting to being old.

Since the turn of the millennium in Britain a man with a moustache has been the exception to the facial hair rule; with men around and over middle age preferring a beard (but predominantly seen clean shaven), and men under middle age seeming to prefer ‘designer stubble’ or intricately preened and sculpted beards in patterns that look like they could only be achieved via the use of a hall of mirrors, an extra pair of hands and specially made templates. Certainly sitting on a commuter train and watching the city-men with their broadsheet financial newspapers, mackintosh coats and briefcases it seems that clerks have returned to their smooth-faced roots.

Recently, though, the moustache has begun to make an annual comeback during ‘Movember’ – a charity which encourages men to show their support by neglecting to shave their top lip for the whole of November in order to raise awareness for prostate cancer, as well as other male forms of the disease. Other than this noble thirty-day period the moustache is consigned to the endangered species list, and possibly soon to history?

The recent boom in the male grooming industry has ensured that remaining smooth faced is far from being exclusive to the countenance of the office sissy, and has rightfully taken its place as a manly art, for which I’m sure we are all thankful.

Now, where’s my scarf; I’ll be needing it this winter…

I had not a clue that shaving would increase my likelihood of suicide. This article must be given to the masses.

If you check out the trinkets and baubles that young girls are into now, you’ll notice the curly handlebar mustache is making a comeback on necklaces, toys and other jewelry. I can only assume the mustache will be making a gradual return over the next 10 years.

Whatever happened to Mantic? It’s been a while since he’s last posted.

Finishing up something special! Will be posting Monday…. 🙂

And here I thought you’ve been working on the railroad, all the live long month. LoL!

I happily sport my handlebar for the cause!

Very entertaining and informative, thank you!

Comments are closed.