Around the time that Mantic59 first started making shaving videos, I discovered “traditional wetshaving” — what I had been doing in high school — but this time I had the benefit of community knowledge, shared via the internet. I dived in.

Evolution

Like lifeforms, human culture continually evolves, and for much the same reasons: reproduction with variation, occasional mutation, and a built-in selection process that results in some entities prospering while others struggle or die off. Cultural evolution is so fast that we can trace the evolution of language, music, fashion, technology, and so on. In this piece I take a look at how traditional shaving has evolved over the past decade and a half.

I shaved in high school and hated it, and once I was away at college I immediately grew a beard, and I stayed unshaven (but trimmed) for a little more than 30 years. When I resumed shaving, it was with cartridge razors and canned foam, and I found I still hated it, though I did not nick myself so much as I did shaving with a DE razor in high school. But what a boring, tedious chore! But then I discovered that traditional wetshaving was still a thing, and there were online forums for learning and online stores with equipment and supplies.

I learned, from others and from my own experiments, and I participated as the shaving world evolved over those years, a Cambrian explosion of new tools and products. Here’s what I saw, in these domains:

- Efficiency – personal changes

- Skill – again, personal change

- Blades – personal, but also the tool

- Razors

- Brushes

- Soaps

- Vendors

- Mission

Efficiency

As with any skill, paying attention, correcting errors, and repeated practice increase efficiency. When I resumed traditional shaving after three-plus decades of not shaving, I was slow — mainly because I was being very careful, paying close attention to blade angle, razor pressure, stroke direction with respect to the grain of my stubble, and so on. And at that point, doing things right took time — loading the brush, for example. It was quite a while before I could readily load a brush in 10 seconds.

I started timing my shaves. When I first resumed shaving, 25 minutes from start to finish was typical. (Novices who have to get an early start in the morning might want to shave in the evening in the first weeks of learning the skill.) Every few months, I would again time my shave, and the time required steadily dropped. The decrease at first was rapid, then slower. Ultimately, a good shave took 5 minutes, and that hasn’t changed for quite a while. (I do recommend timing your shave at least annually, though in the first couple of years it’s interesting to do it every few months since that is the period of fastest improvement.)

The odd thing is that the subjective time never changed: it took as long as it took, and I was paying attention and involved in the activity so I didn’t notice the time, only what I was doing. I never rushed myself — shaving in haste is a mug’s game — and I never dallied, so it always felt like the same amount of time. The clock told a different story.

Skill

Clearly, greater efficiency was the result of greater skill, but I noticed improvements in skill in other ways. Nicks occurred less and less often. I didn’t get so many as in high school, but at the very beginning nicks were not so rare as I would have liked. But the frequency of nicks dropped quickly once I learned that the best way to maintain a good blade angle was to focus on keeping the edge of the cap in contact with the skin and ignoring the guard. (Nicks are almost always due to bad blade angle, though excess pressure can contribute.) The optimal blade angle is close to the angle at which, if you move the handle slightly farther from your face, the razor would be riding on the cap and the blade would cease cutting.

Blades

After I resumed DE shaving, I was at first sensitive to differences in brands of blades, but now I use a variety of brands and they all seem to work well. Partly that’s due to improvement in my skill, but partly it’s because I have gradually found through experience which brands of blades work best for me, and I use those brands. I do think it is important to try a variety of brands, and occasionally I still will try a new brand (most recently Treet Platinum because of a Sharpologist article — and it is indeed a very nice blade for me). Over time one will accumulate a stable of “good” brands, and blades are no longer an issue. (It still seems to be true that a brand that is good for me may not be good for you — that difference could be skill level, but probably it’s because of differences in skin sensitivity, beard toughness/thickness, razor used, prep routine, and even the hardness of the water.)

Double-edge blades themselves have not changed all that much. The big change was back in the 1960s, when stainless steel appeared on the blade scene, and Wilkinson Sword discovered that coating stainless blades made them much more pleasant to use — and patented that technology. Once the Gillette company had to license another company’s technology and thus pay royalties to a competitor, Gillette set itself to find a solution — and led to the development of multiblade cartridge razors, whose patents Gillette owned.

When Gillette moved to focus on multiblade cartridges, much of the manufacturing equipment for double-edge blades was purchased by companies in countries where double-edge blades were still the rule, though Procter & Gamble, which now owns Gillette, does continue to make some double-edge blades (in other countries, including Russia), and they make very good blades, such as the Gillette 7 O’Clock family (whose SharpEdge — yellow pack — is a favorite, Astra Superior Platinum, the very pleasing Gillette Silver Blue, and others).

Some worry that double-edge blades will be discontinued altogether, but now there’s a demand for DE blades, and where a demand exists, some businesses will find a way to make money by meeting that demand.

In the meantime, we enjoy a broad selection of excellent brands of blades sold at modest prices — especially compared to multiblade-cartridge prices, which must cover on-going (and substantial) costs of marketing and promotion.

Razors

I’ve discussed how things changed as I gained experience, but I also see changes in products as their makers gained experience. A decade and a half ago vintage razors were among the best available, though certainly modern brands (Merkur, Edwin Jagger, Mühle, and others) were (still) making DE razors. But then small independent vendors began to bring newly designed razors to market. Demand drives businesses and innovation, and the increased popularity of traditional shaving resulted in a growing demand for razors — and vintage razors are no longer made. Increasing demand with a fixed (and even shrinking) supply made prices of vintage razors start to climb.

The first new razor by a new company that I encountered was a razor made by iKon razors, and their first model gave a rough shave — but their second razor was much better. Almost all their subsequent models give a lovely shave (except, for me, the OG-1: uncomfortable, though efficient).

Then came the Weber Razor, and their first model was strikingly good. (The Sharpologist article at the link explores what was happening in the DE razor market.) And after Weber, other modern double-edge razors began to be launched. Over the years razor quality has steadily improved as new vendors and new models increased in number. More and more frequently, a new razor model — perhaps even one from a new vendor — will be both comfortable and efficient, leapfrogging the learning curve the first modern razors followed. (I particularly recall Fendrihan’s first stainless DE razor — very rough — and then their second, the excellent Fendrihan Mk II, an extremely comfortable and extremely efficient razor at an excellent price for stainless steel.) Clearly the fund of knowledge about how to make a good razor had grown, with manufacturers benefiting from accumulated experience.

It wasn’t long before modern razors were better (on average) than vintage razors. That’s no great surprise: in technology, it is not unusual for later generations of a product to be better than earlier generations because later products are specifically designed to be better than earlier models. No one wants a new model that’s worse than the previous one.

When major manufacturers abandoned double-edge razors (because profit margins on DE blades were as thin as the blades themselves — because (a) patents had expired that resulted in (b) more competition), they focused on proprietary, patented multi-blade cartridges. With that change, R&D on double-edge razors abruptly ended.

But when new vendors entered the market they began competing for a new generation of customers. Unlike back in the day, these new vendors had tools like computer-aided design and computer-aided manufacturing, and their experimentation, experience, and innovation quickly resulted in razors that felt and performed better than those of yesteryear — on average. (Some old razors still match modern performance — the vintage Merkur white bakelite slant, for example, or some models of the Apollo Mikron, whose design descendent is the Merkur Progress.) Certainly some new razors are uncomfortable or inefficient, but on the whole we are in a golden age of double-edge razors. (Few razors are both uncomfortable and inefficient, because such razors don’t survive in the market. Thanks to the internet, communication among consumers is quick and easy, with many shaving forums and blogs, and sites such as Reddit and Quora.)

Some new razors are revivals of old designs — for example, Fine Accoutrements made two slants, one in ABS plastic and one in aluminum, that were tweaks on the Merkur white bakelite slant (and I do love a slant), and Phoenix Artisan has come out with a number of razors based on from classic designs. But there were also new designs, from Rockwell, Italian Barber, Henson Shaving, and others: excellent feel and performance from new, totally non-vintage designs.

I ultimately sold off my collection of vintage razors and now have only razors made within the past decade or so (with a couple of exceptions — for example, that wonderful vintage Merkur white bakelite slant).

Brushes

The big change in brushes has been the rapid improvement in synthetic bristles. The first synthetic shaving brushes used nylon bristles, like those you might find in a whiskbroom: thick and stiff with flat-cut ends. Then Omega came out with their S-series (“synthetic boar”), with finer and more flexible bristles. Those had barely come to market when the angel-hair/Plissoft knots appeared: very fine bristles in a dense, soft knot. In the meantime, Mühle was beavering away at making a synthetic knot that was like a badger knot — not just in appearance, but also in feel and performance.

As a result of this rapid evolution, today one can buy a perfectly good and satisfactory shaving brush for $10, sometimes less, because those brushes use synthetic knots — and because they are manufactured, production volumes can readily be ramped up, driving down unit costs — totally unlike badger pelt production. As a result, synthetic brushes are displacing badger brushes.

Boar brushes use a more readily available natural bristle — thus the lower prices of boar brushes compared to badger brushes — and so boar competes better with synthetic brushes in price, plus boar has its own feel on the face. Boar brushes, though, must be soaked before use and must be broken in, so synthetics do have a slight edge. Still, my Omega Pro 48 (10048) [Ed. note: Amazon affiliate link] remains one of my favorite brushes, and its price remains low. (If you get one, for the first week load it with soap and build a lather in your palm, then rinse out the brush — hot water until clear, then cold water — shake it out excess water, and stand it on its base to air dry. After a week, it will start to hold lather instead of killing it, and after two to three weeks, it will be a pleasure to use.)

Soaps

One of the big changes over the past decade and a half has been the blossoming of artisanal shaving soaps, with some now being large operations. Los Angeles Shaving Soap Company was an early trail-blazer and contributor of knowledge, with many other soap-makers springing up. There was a rush of experimenting with soap formulas, with fragrances, and even with packaging (for example, pucks that were 5” across — a nice large surface for loading the brush, but a size not so amenable to shelf storage).

At the start of the period, the traditional mainstream shaving soap manufacturers, most producing triple-milled pucks, were dominant. But the many small soap makers, trying this and trying that, and constantly working to improve their soaps and to compete successfully in a vigorous market of well-informed enthusiasts, gradually eclipsed the traditional (and less agile) large soap makers. And these small manufacturers have continued to experiment and to improve their soaps. In recent years ultra-premium shaving soaps have become available from Phoenix Artisan (their CK-6 soaps), Declaration Grooming (their Milksteak formula), Grooming Dept (a handful of formulas: Nai, Kairos, and Mallard), Ariana & Evans’ excellent soaps — and others. I am quite fond of Van Yulay soaps with their interesting variety of unusual ingredients.

In the meantime, some of the old mainstream houses outsourced soap production and downgraded formulas — perhaps due to the unremitting pressure on publicly traded companies to increase profits. However, some (D.R. Harris comes to mind) continue to make a fine product. But a static product will lose ground to products that continually evolve because of ongoing experimentation, innovation, and improvement. A fast horse easily outpaced early automobiles, but cars can get faster and horses cannot. Big corporations are like massive cargo ships: they move a lot of product, but they cannot easily or quickly change course — for one thing, their massive customer base is often resistant to change (cf. New Coke).

Vendors

In the early years of traditional shaving’s renascence, those seeking the products they needed could not find them in most mainstream stores — department stores, drugstores, cutlery stores, men’s stores, and the like. Those vendors didn’t carry “old-fashioned” products because, though there was a some demand, it was not concentrated by locale but scattered across the country. Although some stores had good stock for a traditional shaver, they were few and far between. Smallflower / Q Brothers in Chicago, Pasteur Pharmacy in New York… Great if you lived there but, until the internet, not a general solution.

Soapmakers sold their own products directly — and you can still order from makers like Wholly Kaw, Chiseled Face, Soap Commander, Catie’s Bubbles, Stirling Soap Company, Barrister & Mann, and others — and as the years have gone by most of those have expanded to sell a full line of shaving and grooming products, though others, like Mike’s Natural Soaps, stick strictly to soaps.

And here again the internet played a strong role — not only did it provide a community of experience and knowledge-sharing, but it also offered vendors and a scattered customer base a quick and convenient way to interact directly. Em’s Place was a pioneer — a well-stocked shaving shop available anywhere you lived. Other early on-line shops included Bullgoose Shaving, and Razor & Brush (now gone), and West Coast Shaving, now a shaving powerhouse.

Maggard Razors came in after the first wave but has grown to a strong shop with a broad selection of shaving products, including some of their own brushes, soaps, razors, and aftershaves. I’ve mentioned earlier Fine Accoutrements, Phoenix Artisan Accoutrements, and Declaration Grooming. And new shops — The Razor Company, for example — continue to be launched.

Italian Barber is an old-timer and still vigorous, bringing out his own line (under the name “RazoRock”) of brushes, soaps, razors, and aftershaves — including some very nice products indeed. The Stealth slant (no longer available, alas) was a marvellous slant based on the Merkur white bakelite slant, and the Baby Smooth is one of my favorite razors and an ideal razor for a new DE shaver.

Like Fendrihan, Italian Barber straddles the US/Canadian border and serves both countries. Canada in fact has a number of excellent online shaving shops: Top of the Chain, Classic Edge, and others, including Kent of Inglewood, which has a chain of stores in addition to the online shop.

It is thanks to small-shop online vendors that traditional wetshaving was able to grow from isolated hobbyists into an increasingly large demographic that supports a range of healthy businesses. Some of those formerly small shops are now substantial enterprises, and the movement is clearly having an impact — recently Gillette has brought not one but two new double-edge safety razors to market.

Mission

I’ve seen a change in what is viewed as the mission of shaving. Decades ago — in my high school days and the decades before that — the point of shaving was to remove stubble to make the skin smooth again, and that was how ads were pitched.

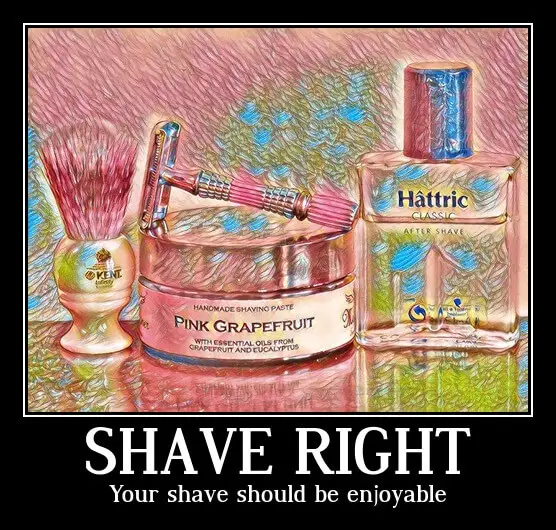

When DE shaving started to become popular again around the turn of this century, the mission grew somewhat: a clean, close shave was still a goal, and a cartridge razor and canned foam could achieve that fairly well. What traditional shaving brought to the party went beyond a good result. Traditional shaving also made the shave enjoyable. It was an example of mission creep: a “good shave” now also included having a pleasurable experience, enjoying the feel of the brush, the fragrance of the lather, the comfort and efficiency of the razor, along with the aesthetic/nostalgic pleasure of finding and using grand old razors. (For many who started the move toward traditional wet shaving, these were the razors of their youth.)

In recent years men, encouraged by the cosmetics industry, have become more conscious of grooming and self-care, and that new awareness has pushed shaving’s mission to now include skin care. In addition to a good result and a pleasurable experience, men increasingly want shave products — pre-shaves, ultra-premium soaps, aftershaves, hydrating gels, and the like — that treat their skin with kindness and respect, improving skin feel, appearance, and health.

Leisureguy — Michael Ham — is the author of Leisureguy’s Guide to Gourmet Shaving the Double-Edge Way, the 7th edition of his instructional guide for those new to traditional shaving, a book that often serves as a gift to a man who must shave but hates it. His blog, Later On, includes posts on a wide variety of topics — its motto is “A blog for those whose interests more or less match mine” — and always includes his shave of the day, which from time to time includes reviews of new products and new realizations about old products.

Very good article. Spot on. Keep em coming

What a terrific article. I really enjoyed learning about the evolution of shaving products and the different companies catering to the wet shaving community.

As always from Mr. Ham, very well written and thought out. It’s hard to believe how long it has been since the early days of the wetshaving “revolution” and how much the movement has grown in the past decade, but it feels like there is still huge potential for continued growth.

Thank you for your kind comment. I agree that there is ample room for more innovation in shaving products, and we’ll likely see continuing new development as demand increases. Demand depends on a lot on word of mouth: those who have experienced the pleasure a good shave can bring telling people who trust their testimony.

The key is to switch the paradigm: to go from the purpose of a shave being to remove stubble to the purpose being to provide a pleasurable experience (while also, by the way, removing stubble). It’s similar to the paradigm shift from eating (fuel for the body) to dining (a pleasurable experience for all the senses — that, by the way, also provides fuel for the body).

Comments are closed.